Cinema and Cubism

You might not think about it, but photography had been shaking up the image making world starting roughly in the mid-1800’s. By the late 1800’s film was a brand new idea coming into vogue at the time of Cubism.

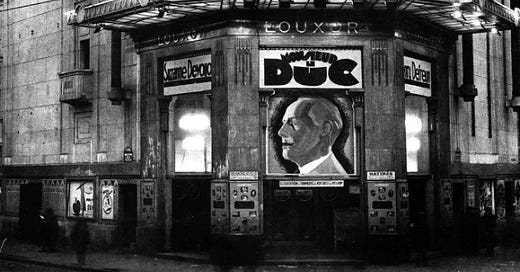

Among the very first patrons of the nascent cinema in Europe were the painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In 1896, Picasso (in Barcelona) had attended the first showings of the new wonder; he was fifteen years old and an instant cinephile. Braque (in France) had also attended cinema from early on. As the new century moved in, a ubiquitous film culture developed. In France, cinema was declared part of the national patrimony by 1907. When Braque and Picasso met in Paris that year they were both already deeply engrossed in the city’s established cinema culture. Together the two artists realized that any new structure of vision (which was their mutual ambition) depended upon engaging movement, as proposed by cinema. Film’s sense of unrestricted possibility, its syntax of radical juxtaposition fostering freedom from spatial and temporal constraints so as to rearrange events at will—all these made cinema an irresistible challenge to painting. Picasso, Braque, and Early Film in Cubism 1. The Idea of Multiple Perspectives

Film introduced the concept of capturing reality from multiple viewpoints by using different camera angles and editing techniques. Cubism, led by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, mirrored this idea by depicting objects from several perspectives simultaneously. The ability of cinema to shift between various angles in a single sequence influenced Cubist artists to think beyond the traditional single-point perspective. They began to break down objects into fragmented planes that represented multiple viewpoints in one image.

2. Movement and the Representation of Time

Cinema's ability to depict movement and time provided artists with a new model for how dynamic motion could be suggested in visual art. In Analytical Cubism (1909-1912), the depiction of subjects in a fragmented manner reflects an attempt to show the passage of time and the experience of movement. This approach resonates with how film uses a sequence of frames to capture motion over time.

Cubist paintings, such as those by Braque and Picasso, often give the impression of overlapping temporal moments within a single static image, similar to how film uses techniques like slow motion, quick cuts, or multiple exposures to manipulate the perception of time. The Futurists, who were closely linked to Cubism in the broader context of modern art, took inspiration from both Cubist principles and cinematic motion, further highlighting the shared exploration of depicting movement.

3. Fragmentation and Editing Techniques

The fragmentation found in Cubism parallels the editing techniques used in film. Just as a film editor cuts and splices different shots to create a coherent narrative or evoke a particular rhythm, Cubist artists fragmented and reassembled forms on the canvas. This approach to breaking down and reconstructing visual reality was influenced by the early cinematic experiments with montage, where sequences were edited together to create new meanings and sensations.

The influence of film's visual language can be seen in how Cubist works, like Braque's Violin and Palette (1909), present fragmented forms and overlapping planes. This effect is similar to how cinema uses cuts, fades, and superimpositions to transition between scenes, giving the viewer a sense of continuity and disruption simultaneously.

4. The Influence of Early Avant-Garde Films

The development of Cubism occurred alongside the rise of avant-garde films that experimented with abstract forms and non-linear narrative structures. Early experimental filmmakers, such as Georges Méliès, used techniques like stop-motion and trick photography to create visual effects that broke away from traditional storytelling. These innovations resonated with Cubist artists who were seeking new ways to represent reality beyond the constraints of naturalistic depiction.

Artists like Fernand Léger, who was associated with Cubism, took inspiration from cinema's ability to present fragmented, rhythmic sequences in films like Ballet Mécanique (1924). This film, with its mechanical rhythms and abstract compositions, reflects the Cubist fascination with the dynamic interplay of shapes, much like the fragmented and overlapping planes in Cubist paintings.

5. The Influence of Popular Culture and Technological Modernity

Cubism emerged during a time when technological advancements, including cinema, were reshaping society's experience of the world. The novelty of moving pictures and the spread of cinema as a popular form of entertainment introduced a new visual culture that impacted how artists perceived motion, space, and representation.

The rapid growth of cinema contributed to a broader cultural interest in mechanical movement, speed, and visual fragmentation, themes that are present in Cubist artworks. The fascination with modern technology, including film, inspired artists to push the boundaries of how reality could be depicted, leading to a more abstract and innovative approach to visual representation.

6. The Role of Picasso's Engagement with Film

Pablo Picasso, one of the pioneers of Cubism, was directly involved with cinema in several instances. He worked on set and costume designs for Jean Cocteau’s films and other theatrical performances that incorporated cinematic elements. This involvement exposed Picasso to the ways in which film could manipulate visual perception and representation, likely influencing his approach to painting.

Furthermore, Picasso's interest in film was part of a broader engagement with various forms of popular entertainment, such as photography and music hall performances, which shared cinema's focus on dynamic movement and shifting perspectives.

7. Parallels in Avant-Garde Art Movements

Cubism’s development was part of a larger movement in modern art that was influenced by cinema and vice versa. Movements like Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism also drew heavily from the visual possibilities introduced by film. These movements often overlapped with Cubism in terms of artists, ideas, and methods, contributing to a cross-pollination of techniques. The interplay of film and modern art thus helped to shape Cubism's approach to depicting fragmented reality.

Conclusion

While Cubism was not solely inspired by film, the emergence of cinema certainly played a role in shaping its development. The idea of presenting multiple perspectives, capturing the sense of movement, and exploring fragmented representations of reality were shared goals between early filmmakers and Cubist artists. The parallel growth of Cubism and cinema reveals a mutual influence where each medium borrowed from and contributed to the evolving visual culture of the early 20th century.

Here are some references that discuss the influence of cinema on Cubism:

Books:

Antliff, Mark, and Patricia Leighten. Cubism and Culture. Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Explores the cultural context of Cubism, including the impact of modern technology and cinema.

Golding, John. Cubism: A History and an Analysis, 1907-1914. Harvard University Press, 1959.

Discusses the visual innovations of Cubism and parallels with contemporary cinematic techniques.

Arnason, H. Harvard, and Elizabeth C. Mansfield. History of Modern Art. Pearson, 2013.

Provides a comprehensive overview of modern art movements, including Cubism, and their connections to cinema.

Elder, R. Bruce. Cubism and Futurism: Spiritual Machines and the Cinematic Effect. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018.

Examines how the fragmentation of form in Cubism relates to cinematic techniques and modern technological culture.

Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932. Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Covers Picasso’s engagement with cinema, set designs, and how these experiences influenced his artwork.

Journal Articles:

McQuillan, Nicola. "Cubism and Cinema: Fragmentation and Movement." Art History, Vol. 21, No. 3, 1998, pp. 312-335.

Analyzes the influence of early cinema on Cubist representation of movement and multiple perspectives.

Leighton, Patricia. "The White Peril and L’Art Nègre: Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism." Art Bulletin, Vol. 72, No. 4, 1990, pp. 609-630.

Discusses Picasso's exposure to new visual media, including film, as part of his artistic development.

Fraenger, Wilhelm. "Cubism and Cinema: The Relationship Between Painting and Film." Modern Language Review, Vol. 45, 1950, pp. 324-338.

Investigates how Cubist painters were inspired by cinematic techniques, including montage and multiple angles.

Documentaries and Films:

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies (2008) - Directed by Arne Glimcher.

A documentary that explores the relationship between early cinema and the development of Cubism, featuring commentary by artists and filmmakers.

Ballet Mécanique (1924) - Directed by Fernand Léger.

An avant-garde film that reflects Cubist principles in its fragmented, rhythmic composition.

Online Articles and Resources:

Tate. "Cubism." Tate Modern, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/cubism

Provides an overview of Cubism, with sections discussing the influence of modern media like cinema.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Analytical Cubism (1909-1912)."

https://www.metmuseum.org

Offers insights into how early Cubist artists interacted with new visual forms and techniques.

These sources provide a variety of perspectives on how cinema influenced the development of Cubism, addressing aspects like fragmentation, movement, and the representation of time.